The Soul, a rare festive day

by Arnaldo Colasanti

In old times philosophers taught that the ‘image’ is imago agens: the image, rather than a representation, is that which acts in us as ‘world’. All the paintings of Konrad Mägi exercise a precise and clear action on our gaze: it is the world that is looking at us. This act of looking has a certain passiveness. We don’t choose to look or what to look at. Something else is happening. The landscape (the most frequent subject of Mägi’s work) is the vision, we should say the display of nature, a nature that holds back itself, and only in that form can give itself as real. The passiveness of the gaze is, therefore, a way of caring. He who looks, rather than being engaged in an exercise of knowledge, lives a very strong and direct experience, a tactile contact, a physical and at the same time imaginary ecstasy of the world that happens before his eyes. This passiveness of experience is not something abstract: the imagines agentes are a measure of the surrending of our souls to sheer emotion.

Reasoning would tell us that this emotional encounter would imply a kind of reconciliation. It is not the case: the emotion we feel is not relief. There is nothing in Mägi’s work that is reassuring: above all nothing is allusive, there is no symbolic code of hidden meanings. Rather, we could state the contrary: the first meaning of the experienced emotion is that the painting looks at the world with hunger, is not seeking the equilibrium of a narration. It is an unsatisfied, tense and nervous painting, a painting that devours that world which in turn is giving itself in its totality. Mägi is not dominating what is before his eyes, he does not want to find or offer a logic explaining the connection between the inward and the outward. I repeat: in his painting nothing guarantees the equilibrium of the representativeness of reality. In fact, if we can say that his painting is hungry for the world, we can also say the opposite, that the same world, the living images of the landscapes, act with violent energy throwing themselves in the painting, a painting that rather than shaping is being shaped.

The dynamic relation between the nature and the gaze of the painter may suggest an impressionist paradigm. And that is correct, impressionism is a fundamental source for Mägi’s painting. But if we stop here, it would be taking a narrow view. French impressionism, especially in Cézanne, is always the construction of a perception or of an impression that has the strength to become the rationality of a pictorial style capable of giving a reconstruction of reality: in other terms, historical impressionism is an architectural paradigm. Mägi’s work takes, instead, another direction. His impressionism and, in general, the lesson of modernism between the end of nineteenth and twentieth century, is characterized by a strong swerve, by an excruciating diversity that marks the real nature of his painting. There is a hunger in Mägi (which seems shared by the landscape, where the gaze of Nature and that of Painting stand in front of each other), which is a living hunger : in the violence of the encounter we recognize the extreme form of a testimony, we could say that we are in the presence of the very condition of a ‘survivor’. In order to trace the meaning of this paradigm we suggest a phenomenology that describes the peculiarity of the pictorial experience. One. Mägi’s painting forces a radicalness in the act of observation. He who is watching is not seeing the landscape (I intend the rationality of nature), instead he sees the modus, the essential position of a spiritual principle. To paint, to be an artist, means to put oneself in a condition of singularity, and therefore of dissimilarity, from the language of mimesis. The painter, devoid of historical or social relations, stands alone in front of the landscape, which shows itself not as one of the possible shapes of reality, but as the only natural landscape possible. Two. To have a living hunger, a hunger that forces the I to turn into a singular naked individual (exactly the modus of a pure soul), means to accept, before any act of choosing is made, a pictorial language that is never evaluative but is, instead, defenceless, immediate, frontal. The shared violence (by the act of painting and by the images of the world) leads to a mutual and symmetric attraction. That which denies to the act of painting the possibility of memory (mimesis or melancholy), offers the elemental form of an experience where the present instant of contact is defined by the void, by the radical capacity of oblivion, which is typical of the testimony, of the nakedness of the survivor. Such a consideration becomes clear when we recognize the status of abstract art to Mägi’s work. This is certainly true: abstractionism, as well as impressionism, are at the source of his painting. But, even in this case, if we were to assign Mägi’s work to the historical movement of abstractionism, we would reduce the complexity of his painting. Mägi’s work is something different, something that goes beyond, even when compared to abstract art. And so, what else? The solitude of the pictorial moment, in which the gaze that sees is already the unrepresentable solitude of the natural landscape, is a solitude of a violence – I insist – that is reciprocal, so that it’s impossible to distinguish between the subject and the object, between the artistic language and the painted landscape. The truth and the strength of Mägi’s art come before the rationality of impressionism and the objective geometry of abstractionism. That is to say: Mägi’s modernism is the incision, the axe of a testimony, not the ethical choice but the radical spirituality, the pure legacy of an unintelligible secret belonging to the human beings and the world that appears before the eyes. In conclusion, at the basis of Mägi’s art is the great, vertiginous emotion of a mystery that is before all symbols.

Three. We have stated that the Mägi’s painting is an experience marked by a double solitude: the relation between the subject and the object comes to an end; the language of dialectic is impossible. The idea of totality (one of the paradigms of European art: to paint the totality of reality) or the idea of infinity (one of the poetic cornerstones of western painting: art as perpetual expression) are replaced by an absurd but extremely powerful absolute, as a state of a final and unaccountable ecstasy. In this perspective, another source for the understanding of Mägi’s work, expressionism, is important but not essential. This is to say that ecstasy is not to be interpreted as the infinity of a language ‘acted’ by a revelation. The ecstasy of Mägi’s painting is, rather, a practise of un-knowing, since of all that we see we know nothing and can’t say anything. This exercise is again the void of nakedness and its radical vertigo. If when we speak of ecstasy we are not talking about a religious experience, we should equally avoid the trap of a stereotype, that of an icy and indifferent North, as if the I that is seeing is on the threshold of shamanism. There is no doubt that Mägi has spoken out loud saying that he was a man and a painter of the great North. But following this path we would leave his art at the periphery of nineteen’s century painting. And we would be wrong.

When our experience as lectors (and a painter is the first lector to ‘read’ the landscape) takes us towards the illegible planes of language, what is left to us, if not a feeling that has no boundaries, no logic, the feeling given by an extremely powerful energy that strikes us from the light of the painting? And if this is so, how could we define this experience of the absolute without the frightening but marvellous term of emotion? This emotion to which we surrender when looking at the art of Mägi has the same absolute fixity of a painting by Marc Rothko, the dream we experience in the Four seasons or the silence we feel in the Houston Chapel. All we can do is cry. But wait, these tears are not shed because of an emotion of nakedness experienced in front of the beauty of the painting. The emotions and the myriads of colours of Mägi do not belong to the aesthetics of romanticism. The zeroing of knowledge, the heart made naked of the pictorial language, the triumph of the vision of the landscape, are all suggesting the presence of a great virtue, the acceptance of all that is nature, the acceptance, first of all, that the painter cannot understand. Only in this virtue, attempted, experimented throughout all his life, lies the deep emotion of Mägi’s art. This is a point that I would like to stress: the virtue of being innocent, or maybe going back to a state of innocence, in the absolute nakedness of things, is the emotion derived from the belief that even death and life won’t hurt anymore, that they won’t be indifferent and alien deities, but perhaps sisters, daughters, mothers.

I am sorry to have imposed on you these boring pages on the theory of the act of seeing. I can’t imagine something worse, especially during a conference. But I would like to ask a question: the vagueness with which art historians have written about Mägi, using all the possible categories of modernism (from neo-impressionism to fauvism, from expressionism to abstractionism and symbolism, someone even talked, maybe in an overstatement, of cubism), is this vagueness or not the proof of a simple fact, that the art historians have difficulty in confronting a deep poetic feeling? Indeed, they end up choosing the most convenient strategy. There is a belief that the fact of placing the artistic experience inside ideological categories and historic taxonomies, using the landmarks of methods and techniques, is the only way to preserve the artistic experience and emotion. But this is just an act of conformism, positivistic in the essence, devoid of strength, passion and beauty! Mägi’s work is the absolute of pristine emotion, it’s a definite experience, radical, violently poetic, of an art that puts at stake the salvation of the human being: his living hunger before the violence of a world that he doesn’t understand and he doesn’t know how to rule, a world in front of which the human being is defeated even if, in spite of everything, he gives away nothing of his humanity. The task of the art critic is not to classify, rather is to find a way to rediscover the moment when the little Enn, visiting a museum with his mum, sees for the first time the Sea Kale. Saaremaa Motif and is touched.

Sea Kale. 1913-1914. Art Museum of Estonia

It is, in conclusion, to find a way to rediscover the meaning of a life-changing encounter: the red thread that unravels from the testimony of a child, of a man, of a lector that embracing a work of art, becomes other.

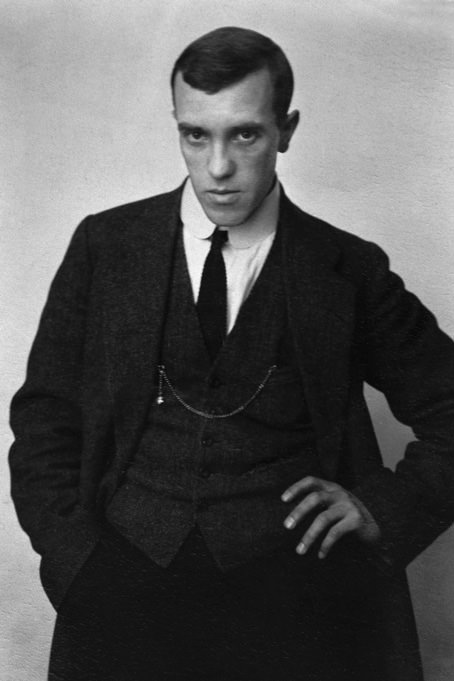

I have read with great pleasure the wonderful monograph written by Eero Epner. Everything flows clearly, like drops of dew on glass. We see Konrad, a lonely man, the carpenter with no family, consumed by the cold, the poverty, by countless sad and dump apartments, moving endlessly from one another in his search of a secret place where he can return. We see Konrad, the rising artist. We feel on our shivering skin his ulcerated stomach, the sickness pulsating inside, his existence of shortages, isolation and difficulties. We know well that to be an artist at the beginning of that century, in the desperate and passionate way Konrad lived his art, must have been something of a superhuman enterprise, something that maybe the present generation will never understand. Still, the accuracy, the respect, the intelligence shown by Eero Epner in his narrative puts us in the condition to rediscover the filigree of a grace: Mägi’s landscapes are empty because they feel the visible fullness of the invisible; the mystery remains untouched because it has a voice. The archipelago of Ǻland, in Eero’s words: “does not force you to feel something… but makes you desire that it never ends”. The work of Konrad Mägi is not a landscape depicted by the work of the light: it is in itself a speaking subject that penetrates us; it is a fullness of the image, always poetically violent, that forces itself upon us, leaving us astonished and in awe of its strength, even when its revelation continues to be an innocent embrace, returning us to our capitulation in front of the great secret of life.

Let us look at the Landscape with a Red Cloud.

Landscape with a red Cloud. 1913-1914. Art Museum of Estonia

The perspective is empty because it is upside down. Our gaze doesn’t go to the vanishing point of the light: instead, it is the horizon that is falling on us with the fury of its beauty. We would like to understand the glory of the setting sun; the true relations between the burning clouds of the sky and the waves of the purplish sea, an encounter of lights refracted in lobster-like shades and then in a scarlet swollen with variations that go from yellows to brick-coloured chromatism, we would like to make ours these spatial relations made of colours, from the amethyst that goes flowing in an opaque coral or maybe a dark emerald to certain folds of indigo, a sea that is always sky while everything that flows appears yet to melt as the opposites do in the same moment, in the aquamarine of a white yellow pollen-like colour or in the Persian blue of a black dark-brown tonality, leather-like or immediately light turquoise, tar-like material and pure abstraction. I insist, we should want to understand why the wind that brings that which is afar on to the eyelids is turning following a transverse path along the branching of the trees, along the crab-like vegetation full of the northern light and then along the shades of green of the forests or the dark brown of the scorched lands, the red-purple inside a pearl grey, then the colour of ashes and immediately the slate, like tufts of prehistoric hesitations, the rocks blooming with reflections and glares both orange and bronze, up to the green secrets of the gold, the unreal yellows of the sun-drenched sand. We would like to understand, but, in fact, this reality is only unveiled to us, it is given to us as a legacy, it cannot be disassembled by words, it simply exists: it is all in the moment in which it stays, an absolute, which we look without understanding it. This nature looks for us like a mother; she wants our gaze the same way we want her vision. But this living famished unity confesses without fear the deep emotion for a dialogue of love that must remain unsaid: for a secret that remains a secret. Let’s look at the Saaremaa. A Study found in Enn Kunila’s Collection.

Saaremaa. A Study. 1913-1914. Enn Kunila’s Collection

It would seem that everything flows sliding towards the infinite like in certain pictorial planes of Italian vertigos. But there is more. The colours are softened by short brush strokes. They look like caresses, instead they are sighs. The chromatic order is a system of harmony. Nonetheless, when looking more closely, we come to understand that the rule of this writing is the anacoluthon, while the syntax is a wood of parataxis where emotionally charged refractions are alive and gathering. To say fauves would be a true statement, but it wouldn’t be enough, for it seems very clear that the idea of a vanishing point is for the painter the blooming of a state of nature suspended and present. This is something that doesn’t fit with the normal neo-impressionist style. The becoming of this flowering garden, the richness of a tonalism that absorbs in itself the thousands of realities of the acting images, the imago agens, are again the emotion of a slow returning home, towards a familiar, brotherly, intimate place but also naturally unknown, altogether indefinable in his absolute. So I believe that Konrad Mägi’s painting brings us to say that the only thing that is of value in art is the extent to which it changes our life. With his work the art of the twentieth century remained faithful at its demands of spirituality: at a life that adds to life, at an art that is living image of existence. With his painting the North remains central in the homeland Europe: a land made of centres and open roads, never of borders. Mägi remains my pride, your pride to be European, the love untouched of a child, Enn Kunila, now a man, but always placed in the same moment of beauty, never forgetting that our land, Europe, is a common culture and civilization, it’s the true landscape of our dreams, a land where the art, the poetry, the search of an existential meaning, are really the best and most dignified ways of living.