The reproduction of these works without the express written consent of the owner of the works is prohibited.

DownloadPortrait of a Lady

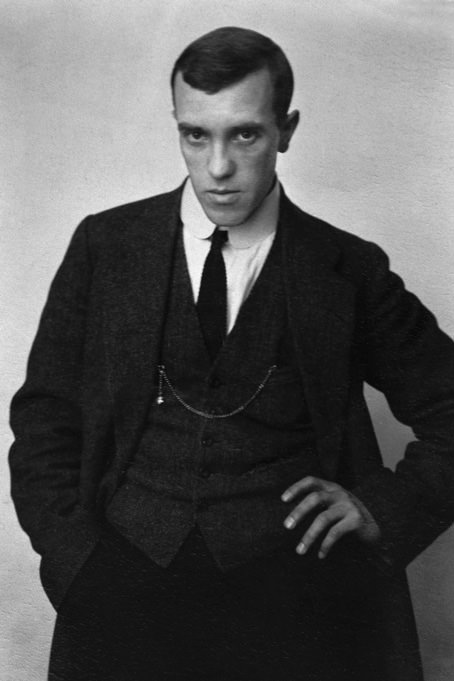

In several ways, this is an exceptional portrait for Mägi, since it features text on the painting surface and depicts a typical motif from Japanese culture not seen before or after in his oeuvre. It is an example of Japonisme, a widespread trend in Western Europe from the middle of the 19th century on, a time when trade relations with Japan became closer and saw the creation of musical, literary and artistic works inspired by Japanese culture.

Mägi was undoubtedly acquainted with Japonisme – it was extremely popular in Paris, with works by Japanese artists regularly exhibited in galleries, Hokusai’s prints being particularly influential. Although a major exhibition of Hokusai prints was held in the city at a time when Mägi was no longer in Paris (1913), it can be said with some confidence that he was familiar with Hokusai and his influences on other artists’ works.

It is hard to say how much Hokusai or other Japanese artists influenced Mägi’s work. Some stylized landscapes drawn in Norway are reminiscent of Hokusai’s prints, and some paintings demonstrate Mägi’s interest in depicting flowers, but Japonisme never stands out starkly in Mägi’s works. And there is still no contextual explanation as to why all of a sudden, he decided to use a Japanese motif in this specific work.

Nor is deciphering the text in the painting of much use. Rein Raud, an Estonian Japanese studies scholar, says elements of Chinese ideograms can be seen in the text but these are not written correctly and contain errors: some information is provided by the kanji text, which is not rendered correctly but with errors: some of the strokes in the symbols are missing and some are out of proportion. According to Rein Raud, a Japan scholar, the top two symbols can be interpreted as alluding to a portrait painted for or on someone’s birthday. The two lower symbols stand for the name “Wada”, a common Japanese surname. But there are no more details about who Wada was or whether the person was real or fictitious.

Yet according to an analysis by the curator and archivist of the National Museum of Western Art, Mari Kezuka, the text is indeed in Chinese characters but the names Kotobuki, Ga and Fuku can also be made out. Furthermore, the meaning of the top letter “T” is unclear and Kezuka theorizes that Mägi may have copied a painting that was important to him. According to her, this is also indicated by the manner in which the character with black hair is depicted: the figure’s right hand does not seem human and the grey colour is too conspicuously different from the tone of the face.

According to Mari Kezuka, the black-haired character is not female but in fact a chigo – young trainee monk who dances in temples and other shrines. This custom arose in the late 8th century during the Heian period when chigos were servants in temples, and also in samurai society, sometimes serving as homosexual partners for adult monks in Buddhist monasteries.

The reproduction of these works without the express written consent of the owner of the works is prohibited.