Konrad Mägi back in Norway. Andreas Trossek

Andreas Trossek reports on the retrospective exhibition “Konrad Mägi: Estonia’s Great Painter”.

26. XI 2022–2. IV 2023

Lillehammer Art Museum

Curators: Nils Ohlsen, Pilvi Kalhama

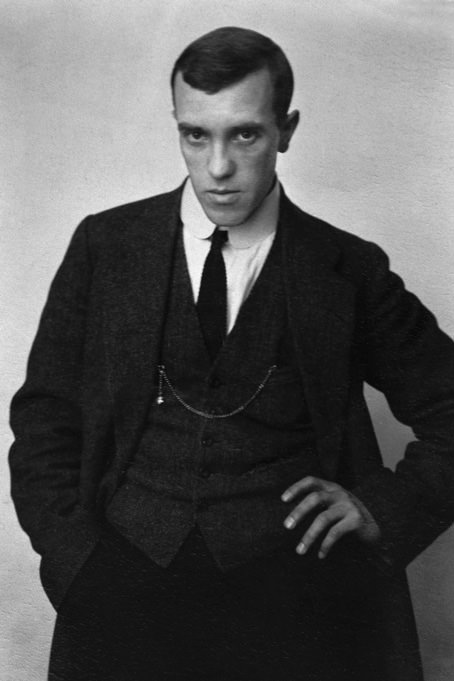

The logbook date is 26. XI 2022. The location is the Lillehammer Art Museum, where the ceremonial opening of the retrospective exhibition of Konrad Mägi (1878–1925) is currently taking place. Who is he? “Estonia’s great painter”, says the second half of the exhibition title, which follows the artist’s name.

I lazily observe the people pouring into the exhibition halls. As a foreign journalist, I naturally don’t know who all the people are that the director of the museum, Nils Ohlsen, is happily greeting, but it is definitely an important event. This is the third and final stop on Konrad Mägi’s posthumous Nordic tour. The retrospective exhibition curated by Pilvi Kalhama has previously been exhibited at the Espoo Museum of Modern Art EMMA (29. IX 2021–23. I 2022) and then at the Copenhagen GL Strand art centre (12. III–29. V 2022), both times under the title “Konrad Mägi: The Enigma of Painting”. Somewhere nearby, among others, the First Lady of Estonia, who has been flown to Lillehammer for this purpose, is preparing her opening speech.

The opening seems to be quite a success; there are quite a lot of people.

Two local old ladies are engrossed in the wall text of the exhibition, the dates summarising the life and work of an artist as yet unknown to them. They read the text on the wall quickly, a little impatiently, deftly bypassing the professional art history lingo. They obviously want an answer to one simple question.

Why? Why didn’t they know anything about him before?1

“Here!” The old lady’s finger points to one specific place in the wall text. In 1944, the forces of the Soviet Union again occupied the territory of Estonia. The era that Estonians call the Soviet occupation began. The Republic of Estonia, proclaimed in 1918, disappeared from the world map for the Western bloc; it no longer existed.

“Here, yes!” They exchange historical knowledge accompanied by lively gesticulations, because Estonia has been on the world map again since 1991. The distance between Estonia and Norway is less than 1000 kilometres; the capital of Norway, Oslo, and the capital of Estonia, Tallinn, are essentially on the same latitude.

After this, the old ladies calmly proceed to the exhibition. They have solved the mystery for themselves.

The life and early death of an artist

Konrad Mägi lived to be 46 years old. By all accounts, he led a relatively unhappy life. Loneliness, money troubles, health problems, broken dreams. Undiagnosed disease(s), early death. A story we’ve all heard many times before – just with different names, and different details. Essentially the same story, though. The story of a suffering artist.

What would it have been like to have been born an Estonian in one of the westernmost provinces of the Russian Empire in the last quarter of the 19th century? It certainly wouldn’t have been a very privileged feeling.

You were inherently foreign to the local Baltic German elite. You were inherently foreign to the Russians representing the imperial power. You were a nobody, a simple peasant from among rural people. To generalise a little – and history allows for a little generalising, doesn’t it? – Konrad Mägi was from the local serf class. Serfdom had already been abolished in these parts with the Peasant’s Laws of 1816 and 1819, but the central government only lifted restrictions on movement with the Passport Law of 1863 (i.e. 15 years before Mägi’s birth). In other words: he didn’t really have any special predispositions for success. Regardless of one’s perspective or how many centuries one looks back, he came from a province, a colony – a land without history, which had never crowned its own kings.

Not only that, even though he was born in his homeland, his mother tongue was not the only language used in most places or circumstances. The ability to more or less satisfactorily speak Russian, which consolidated the Russian Empire, and use Cyrillic script when reading and writing, came later. Estonian belongs to the Finno-Ugric language group, which is much rarer than the Slavic languages, and the written Estonian language has been based on the Latin alphabet since the first attempts at translating the Bible in the 16th and 17th centuries. But as a foreigner by nature, one just has to learn everything throughout one’s life, and there is nothing special or heroic about this in itself; it’s just a matter of survival.

So what image are we left with? A lower class origin, a brief education in a village school, dull subsistence work as a carpenter in Tartu as a youth. An uncompromising desire to travel to the metropolises of the world as an adult to learn to be a real artist – despite the constant lack of money and weak foreign language skills. The inability to break through in Paris, the pinnacle of the international art world at the time (yes, he never learned French). Moderate sales success in his homeland, which only came when it was perhaps a little too late. Concern about the lack of people who appreciated art and the nerve-wracking work in organising and pedagogy. There is no record of any direct descendants. A type unsuitable for marriage, constantly dissatisfied and fickle. However, with considerable capacity for work. Nearly 400 (or more) paintings are known, all completed within the last 18 years of his life.

One life. Only one life to live. One journey that was interrupted… and gave birth to a legend. It is a legend that is larger than life. One among many. A legend about an Estonian artist whose work should be part of European art history.

But did he even sense that time was running out? The style of his paintings is constantly changing: from realistic symbolism and art nouveau stylisation to post-impressionist brushwork (especially pointillism) and an expressionist colour palette. He obviously wanted to move with his times. His (surviving) correspondence is filled with the desire to leave Estonia – to improve in the field of art. Where does this desire come from, his influences?

Just out of interest, where did the upper-class children of Europe go to educate themselves culturally in previous centuries? And what was the name of that tradition, was it the Grand Tour? Where did Konrad Mägi go before his death? When he had already stayed long enough in both Saint Petersburg and Paris, and between these painted Nordic landscapes in Åland and then in Norway? Was it Italy? And did he intend to die?

Maybe not then? Maybe life was still for him even then, during this last remaining Grand Tour… just at its beginning? Maybe even in his forties he felt that he still had time because he had started his art studies relatively late? And maybe all this hindsight speculation would have been for nought if he could just… have visited the right doctor at the right time?

A tour of the museum shop (or how to learn to live with lasting guilt)

Today, almost 100 years after the death of this starving and freezing artist, one symbolic circle has been completed. Konrad Mägi’s name is well-known in his homeland, paradoxically becoming more and more well-known as more years pass since his death. In the 21st century, his paintings quite routinely break all kinds of Estonian art auction records (currently one of them is close to a quarter of a million euros, but it will probably be surpassed soon), a series of thick monographs have been published about the artist, a painting prize named after him is considered the most important in the country, documentaries and theatre productions have been made about his life and work, postcards and fridge magnets, colouring books aimed at children, etc.

Konrad Mägi is currently for Estonia what, for example, Edvard Munch is for Norway, Helene Schjerfbeck is for Finland or Vilhelms Purvītis is for Latvia. The first generation of modernists with a more or less tragic fate from more or less “new” countries on the world map. The firsts will always be first (or so we like to think).

We could always argue – as a way to pass the time, perhaps – whether this narrative model was established by Vincent van Gogh or by some romantic art hero before him, on a historical scale. Either way, some martyred passion is undoubtedly contained in these stories, that’s for sure. The idea that one died for something more, bigger than oneself. Art, for example.

And yet something is always wrong in this repetitious martyrdom. There is something even a little sadistic in this sympathy or psychic identification, in this posthumous recognition and respect with which we gild the creative people who have left us, recite their biographies and celebrate the anniversaries of their birth or death.

It’s as if we, as representatives of the art audience, occupy some strange wait-and-see position. It’s as if we couldn’t possibly share our praise or say even one kind word as a comment on artists who are still (as yet) living. As if we require something extra, some external confirmation of their talent from I-don’t-know-who about I-don’t-know-what precisely. Like a little impatient child who wants their mummy or daddy to tell them the end of a fairy tale before deciding whether it’s worth reading.

As if we were waiting for… the death of the artist? I mean, why are we beating around the bush for so long: that’s what it actually and more accurately comes down to? “An artist should be poor”, “true art is born from suffering”, “the best artist is a dead artist” (and other similar cynicisms, which are especially common these days on social networks and among anonymous internet comments)? Because it is a great pleasure to open the first page of a book fresh from the museum shop, but an even greater pleasure is to close it after reading it.

Knowing how the story ends

The logbook date is 27. XI 2022. On the way home to Tallinn, I’m in a slightly euphoric mood on the train ride from Lillehammer to Oslo airport, precisely because of the mountainous views from the train window. This is a privilege that belongs to the tourist; the locals sitting near me, on the other hand, find what is displayed on their smartphone screens much more interesting.

Indeed, a native of Tallinn like myself does not really know the meaning of the word mountain. In north Estonia, unlike the south, where Konrad Mägi was from, there are actually no real mountains; there are only some occasional rolling landforms, which in the present twilight era of fossil fuel wheeled transport are more often referred to as “bumps-on-the-road-in-front-of-us”, not mountains.

Yet even the beautiful hilly landscapes of south Estonia are no match for Norway’s dramatic natural vistas – mysterious mountains, rapids and fjords, and trees that seem to defy both gravity and our perceived omnipotence of humanity by growing almost vertically from the rocky cliffs directly into the sky. Therefore, on an emotional level, I can completely understand one excerpt from a letter where Mägi says something along the lines of looking at the mountains and clouds in Norway and feeling that this was a place that gods could inhabit. So it is!

Two key themes connect Mägi’s work with Norway: landscape painting and his first important exhibition, almost a solo exhibition. Here he became a real artist, here his career began. He lived here, he painted here – especially in the surroundings of Oslo (which was still called Christiania at the time). He was attracted by the aesthetic appeal of the landscapes here; they triggered something in him, a kind of vertical aspiration and also made the colours and forms “explode” in his paintings. (Or maybe this was down to vitamin-rich blueberries that the cash-strapped artist allegedly subsisted on.)

Konrad Mägi Norwegian Landscape with a Pine Tree 1908–1910 Oil on canvas, 59 x 75 cm

Photo by Stanislav Stepashko Art Museum of Estonia

Mägi lived in Norway from the summer of 1908 until the end of 1910 – he arrived from Paris and then went back to Paris. Successful artists in Paris went to Normandy to paint landscapes, Mägi travelled to Norway for the same purpose. While in Norway, as far as we know, he almost exclusively painted landscapes – “Portrait of a Norwegian Girl” (1909), depicting the actress Gerd Grieg as a child, is an exception that seems to prove the rule. Mägi produced a very large number of paintings in Norway (perhaps around a hundred) – a collection, among which some have become the epitome of Estonian art history, without which it would be impossible to imagine the cultural self-awareness of Estonians (for example, “Norwegian Landscape with a Pine Tree” or “Norwegian Landscape. Bog Landscape”, both 1908–1910), and then the rest of the paintings, which have been lost without a trace.

But that is not all. At the price of sounding a little ceremonial and implementing dull art historical lingo, it was here that his institutional breakthrough into the international art world took place, because here is where his publicly documented career as an art professional began. The famous Norwegian realist painter Christian Krohg (1852–1925), Mägi’s former teacher from Paris, who had been elected the first professor of the newly established Norwegian Academy of Art in 1909, specifically invited Mägi to participate with him in an exhibition that took place in the spring of 1910 at the Blomqvist Gallery. A number of Mägi’s paintings were on display, and one art critic even wrote a few lines about the exhibition in the newspaper Aftenposten, describing Mägi’s use of colour as fun.

“This was Konrad Mägi’s first (and also last) exhibition abroad,” writes Eero Epner, and to pull the rug from under the feet of the excited reader, he adds: “And – that’s it. [—] It’s not tragic. This happened to many Eastern European artists, and even Northern European artists are only now being written into the art history of a hundred years ago (unless they are Munch, but not everyone can be Munch).”2 Although at a certain degree of generalisation – again: history allows for generalisations, doesn’t it? – we could place Munch and Mägi on the same level. Because both of them owed Krohg a debt in a way. (Mägi a little less, Munch… a little more.)

Anyway, later in the same year of 1910, Mägi sent some of his paintings home, and they attracted a lot of attention at the first art exhibition organised by the Noor-Eesti literary group in Tartu. With the money he earned, he could return to Paris again. A total of four review exhibitions of Estonian art were organised by the group (1910–1911, 1912, 1913 and 1914), and a list of canonical modernists began to take shape in the local literary and cultural history.

However, how strange it is to think in retrospect that the landscape motifs painted in Norway have become some of the best-known works in Estonian art history! But yes, it doesn’t really matter in the end because we already know how the story ends – and it ends sadly, with the untimely death of the main character in 1925. And we also understand these historical-political reasons why retrospectives of Konrad Mägi were not organised in the Nordic countries or elsewhere in the free world before.

Art that outlives the artist

What happened next? At the end of the Second World War, almost all the territories that the Red Army’s military boots and tank tracks had crossed during the war – once or twice, whatever, a corpse does not complain or keep count – as part of the anti-fascist coalition were left in the direct or indirect sphere of influence of the Stalinist regime. The fear of the massiveness of the Soviet Union and the possible outbreak of the Third World War outweighed the question of the small nations of Eastern Europe. Entire countries disappeared from the world map as the spoils of war, among others, also Estonia.

Had the artist seen this himself, his fate would probably have been even harsher. According to the dogma of socialist realism, his art represented Western “formalism”, which had to be condemned and for which the artist could even have been deported to a correctional labour camp in Siberia. Since Mägi was the first head of the art school Pallas, founded in Tartu in 1919, it is possible that he would have been stood by a wall for that reason alone. His paintings were kept in closed museum collections almost until the end of the 1950s. By then you were allowed to show some things – preferably within the borders of the federal republic. An “iron curtain” had fallen between his paintings and the free world.

In 1991, this curtain was lifted, but certain walls still remained in people’s heads. Walls of ignorance. Walls of disinterest. Walls of self-centredness. Walls of prejudice.And these walls had to be demolished. Stone by stone. The work that began more than a hundred years ago continues.

The logbook date is 16. XI 1907. Konrad Mägi is in Paris and writes in one of his letters: “There are artists who don’t understand Nordic artists, but I can say the same about many French and other artists. I am a son of the North and everything that is me is nothing more than a part of the whole people and our nature. Wherever I am, the North remains my homeland (in the broadest sense). I like the bleak, harsh northern nature, the bright sunshine [—]. The Parisian artists do not consider us Europeans and often remind us that they are Europeans, while we are “Russians” [—]. All artists should not be forced into one frame.”3

1 Although the artist’s work has been shown at various exhibitions this century, for example in Italy, France, Finland and Denmark, I happened to talk to only one local visitor to the exhibition in Lillehammer who had previously come across his name and work (this had happened at the aforementioned exhibition at EMMA).

2 Eero Epner, Konrad Mägi. Tallinn: Enn Kunila/OÜ Sperare, 2017, p 253.

3 See more: https://konradmagi.ee/et/konrad-magi-kirjad/.

Andreas Trossek is the editor-in-chief of KUNST.EE.

His posting as a journalist to Lillehammer was made possible by the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Tallinn.